How the Creative Arts can Serve Behavioural Change: Memorable, Emotional, Effective

Since 2008 — when Sunstein and Thaler published the book Nudge — the worlds of applied psychology, behavioural science, and economics have been taken by a storm: nudges have been found to be powerful tools to change behaviours otherwise thought as “hardwired” in people’s brains. All of a sudden, governments could get people to pay their taxes more, vote more, and be more civil in the streets; teachers could get kids more engaged; marketers understood that they could save billions for companies by giving people Wi-Fi instead of faster trains. Nudges are understood as small tweaks (to the environment, language, or other types of messaging) that could bring big behavioural changes. Sure, there are a lot of social interventions that are not nudges, strictly speaking (educational programs, policies, big-budget accessibility projects, etc), but it’s hard to tell nowadays. Everything seems to be a nudge.

Jump forwards in time some years to 2022, this year, the year in which I graduated from a Master’s of Applied Psychology. This includes subjects on social psychology, behavioural sciences, health and change, marketing, etc. Of course, it doesn’t include any subject on art. But I’d argue that creativity, art in the most common interpretation of the word, may be an underrated tool for behavioural and social change.

I will present some examples I have learned about over the past years (not academically), and will discuss the subject further as we go.

Install-ing Change

They were lying down, rolling around and waving. One person brought an inflatable canoe.

Ice Watch was just one example of the many environmental projects out of the mind of Ólafur Elíasson. Ice Watch was also a pivotal finding that hastened, with a certain urgency, my research on the relationship between works of art and behavioural change. Placing large ice blocks from Greenland into a public area where people could engage with them, Elíasson put in place a tool for many steps usually considered parts of the path to change: awareness, self (e.g. what person am I?) identity, and perception of social norms (e.g. what are other people doing? What does the majority think of this cause?). Of course, it is difficult to evaluate the impact these installations have had on the audience’s sustainable behaviours, thus a lot of what I am saying is anecdotal or sophistic if you wish. But it follows, in my opinion, a strong logic that should be considered.

Apparently, the connection (his work has) with behavioural science didn’t escape the artist himself:

“I’ve been studying behavioural psychology, and looking into the consequences of experience. What does it mean to experience something? Does it change you or not change you? It turns out that data alone only promotes a small degree of change. So in order to create the massive behavioural change needed [to tackle climate change] we have to emotionalise that data, make it physically tangible.” — Ólafur Elíasson

“Another woman touched it and said ‘wow, it’s really cold!’ Of course she knew this but the knowledge of her hand is so different to the knowledge in our heads.” — via The Guardian

His other works have focused on similar themes, and the same concept of translating issues in tangible reality, but have used other — emotional — forms of dialogue. We are not talking about verbal vs nonverbal communication, rather, the differences between the type of installations.

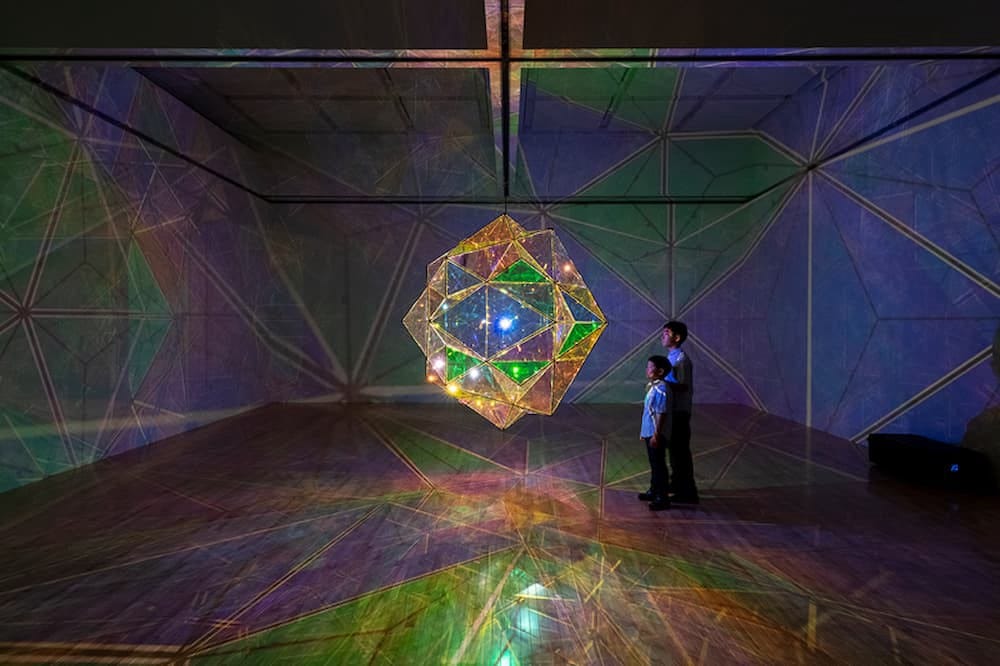

In his famously sublime work The Weather Project, Elíasson recreated the sun out of a semicircle and a mirror (part of the inspiration was the sun’s reflection on water as painted by Edvard Munch). The project was created in conversation about the environment in mind, but what the artist and his team realised soon was how much the art piece connected not only with people’s consciousness, but their behaviour:

What surprised me was how people became very physically explicit. I pictured them looking up with their eyes, but they were lying down, rolling around and waving. One person brought an inflatable canoe. There were yoga classes that came, and weird poetry cults doing doomsday events. — O. E.

Across the years, Elíasson has pushed the limits of spaces and what art can do: he flooded a museum with a pond, and created change directly with Little Sun Lamp.

The Scandinavian genius, however, is not the only one trying to change the world (and behaviour) through art. In fact, in many ways, artists have been, for millennia, striving for change (think about also the role art had to control populations, keep them in “the right faith”, and so on). In dialogue with artists who came before him, Fabio Viale used sculpture and performative arts to send a message to the Italian people and (*forcing myself not to use insults here*) Minister of Interior Affairs, Matteo Salvini. Lampedusa, Italy, has been for years now subjected to a lot of political dialogues and polemics surrounding the large amount of refugees and immigrants from countries subjected to war. Many politicians have often threatened to close borders, and send refugees back.

In the photos below, the response by sculptor Fabio Viale:

I think, from a behavioural change standpoint, this piece might have been a powerful tool for using emotional messaging and relatable symbolism to get to Italians’ consciousness

.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Art Avo to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.